Part 1

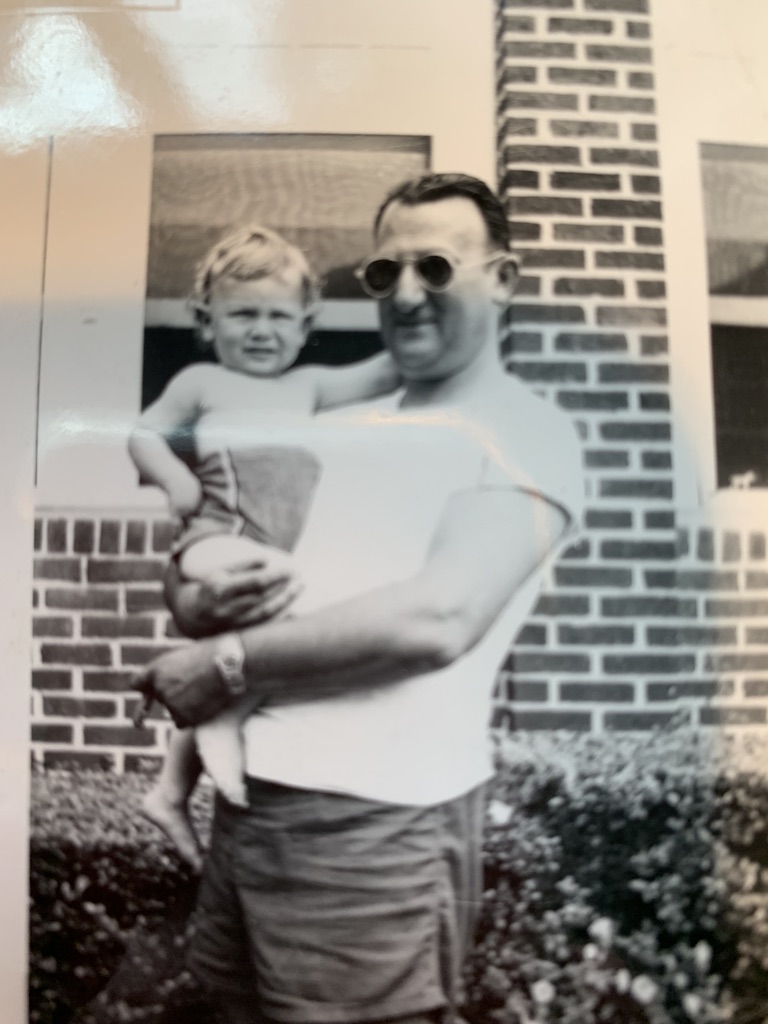

I was born on a hot August night in West Philadelphia. My mother and her two sisters had to take public transportation to the hospital, as my father was off somewhere in Europe fighting the Germans. Well, he didn’t do much of the actual fighting; he was a doctor and so tended to the wounded. He never spoke much about his experiences there. When my dad returned from overseas, having not seen me until I was almost a year old, the family story goes that we were riding in an elevator with the maintenance man in our apartment building and I pointed at that man and said Dadda. I don’t imagine my father was amused. He and I continued to have relationship issues for years thereafter.

My mother struggled giving birth to me, as she often later reminded me. The delivery took many hours and when I finally struggled out, weighed in at over ten pounds. The nurses immediately started calling me Butch, a name that has stuck with me most of my life.

At the time of my birth, my mother and older sister, Linda, were living with my maternal grandparents in an apartment above my grandfather’s pharmacy in West Philadelphia. It wasn’t until a couple years after Dad returned that we moved into our home, a 3-story, brick duplex only two blocks away from Grandpop’s store. My father’s office and waiting room occupied the first floor, and from an early age, I was constantly reminded to be quiet when Dad was seeing patients. I don’t think I ever understood why that was necessary, and always found it hard to comply, and more than a few times suffered my father’s wrath when he ascended the stairs to our second-floor kitchen, his face scarlet red above his bow-tie, yelling about “all the damn noise.” I was almost always either scared of my father or resentful of him. He was a hard man, silent and unsmiling. And given to occasional, fits of rage.

My brother Paul, was born two years after me, and we shared a room on the 3rd floor of our house throughout our childhood until I left for college at 18. We got along together well, rarely fought or argued. We didn’t talk much, except late at night, when we were feeling excited and alive and so couldn’t fall asleep. I guess we were sometimes too loud and laughed too much and Mom would yell up the stairs for us to get to sleep “right now or I’m coming up there!” And still we couldn’t make ourselves stop and eventually up she would come, her footsteps heavy on the wooden stairs. And as scared as we were, at least for me, there was something delicious and exciting in facing what would come. Then Mom would slam open our door (she was a big woman—heavy-handed), and without comment begin slapping at us huddled under our blankets, trying not to laugh which would only make her swing harder. Paul got the worst of it as his bed was closest to the door, and by the time Mom got to me her blows were landing with less force. “I told you,” she proclaimed when she left. “Don’t make me come up here again.” Like it was our fault, like we made her hit us. Which maybe we did, but little by little, the evidence was piling up in my head, that my parents were not my friends. I would not have known at that age how to name what was happening to me, but in retrospect I think I was discovering that in order to be myself, to thrive, I would somehow have to escape my family.

My childhood was not entirely unhappy—far from it. I now realize I was living a very privileged life, never wanting for any of the basic necessities, never hungry, never unsafe. This wasn’t the case with some of my friends and neighbors I later discovered. I even got to take piano lessons when I was six years old, even though I wasn’t particularly interested in the piano. But It was what my mother wanted for me. I knew early on that Mom was grooming me for something, though I was not sure what it was. But I felt the weight of her expectations. I was supposed to be something special; I was supposed to excel.

It didn’t work out that way. At least not in the way my parents imagined, which was that I would become a doctor like my father. On one of my early birthdays, Mom gave me a kid’s book titled , “So You Want to be a Doctor.” It took me a few years ( a lot of years) to tell them squarely that I did not want to be a doctor. I couldn’t stand the sight of blood and wasn’t scientifically oriented. Instead I wanted to be a writer, but I never got that book. Don’t suppose there was one.

Of course none of this matters; it’s just an old man nattering over his life. watching how it unfolded, sometimes wondering how it might have turned out differently. But not in the least disappointed in how it did. I’m a happy, lucky man. And best of all, I know it. Hope my parents knew that in the end.

Leave a comment